Now, the interesting question is whether those lines will keep falling, and what might rise in their place.

More.

Update: For those who don’t know about google ngram. And for a more enlightening case study:

and especially:

Now, the interesting question is whether those lines will keep falling, and what might rise in their place.

More.

Update: For those who don’t know about google ngram. And for a more enlightening case study:

and especially:

Now, I am not sure I totally agree with his reading of the politics, for reasons I’ve tried to spell out elsewhere. But JW Mason does a good job of making a point that has occasionally come up with since the economic crisis drove down interest rates, namely i. that there is no reason to think that real interest rates should be above zero, and ii. when real interests rates are very low, capitalists (qua money owners) have no real function:

Now, I am not sure I totally agree with his reading of the politics, for reasons I’ve tried to spell out elsewhere. But JW Mason does a good job of making a point that has occasionally come up with since the economic crisis drove down interest rates, namely i. that there is no reason to think that real interest rates should be above zero, and ii. when real interests rates are very low, capitalists (qua money owners) have no real function:

Under capitalism, the elite are those who own (or control) money. Their function is, in a broad sense, to provide liquidity. To the extent that pure money-holders facilitate production, it is because money serves as a coordination mechanism, bridging gaps — over time and especially with unknown or untrusted counterparties — that would otherwise prevent cooperation from taking place. [1] In a world where liquidity is abundant, this coordination function is evidently obsolete and can no longer be a source of authority or material rewards.

Back in 2007, Cory Doctorow wrote a short story whose basic conceit was a future in which capital–liquid capital–had truly become obsolete, especially relative to the available human ingenuity, inventiveness and the capacity to make stuff (sigh: yes, yes, i.e. human capital). Low interest rates is one way to make that world happen.

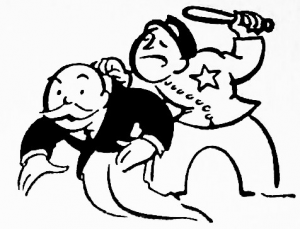

Its easy for egalitarian leftists to get excited about this prospect. Real interest rates that stay consistently below (even very low) economic growth rates would mean the refutation of Piketty‘s grim prophecies. The idea of monocled, top-hatted plutocrats getting crushed under the wheels of history offers the schadenfreude of class enemies losing, with the added zest of partially confirming certain strains of Marxist historicism, in form if not in function.

The defeat of the capitalists, however, doesn’t mean permanent victory for humanity (or the working class, or the multitude, or whatever your favourite representative of eschatological emancipation happens to be). There’s no reason to believe, in a world of low returns on cash, that there won’t be political efforts to hoard the relatively scarce resources that were the source of wealth in Doctorow’s world – education, skills, networks, the preternatural ability to interact with robots. If the last 5000 years are any indication, there are likely to be intellectual movements to justify limited access to the new sources of wealth, as well.

The end of capitalists may mean the end of capitalism as we know it, but it won’t be the end of politics.

Over on the New York Times economix blog, an argument for high taxation and robust government spending using data from, of all places, the Republican-supporting Heritage Foundation in response to those who think that those who pay low taxes are ‘lucky duckies.’ As an example of the cute analysis:

Equatorial Guinea: According to the Republican-leaning Heritage Foundation, those who live in this small country in sub-Saharan Africa are lucky duckies indeed. Because of recently discovered oil deposits, the citizens of Equatorial Guinea pay less than 1 percent of the gross domestic product in taxes. The comparable figure for the United States is 26.9 percent of G.D.P., according to Heritage.

However, Equatorial Guinea doesn’t seem to be a very pleasant place to live. The people are poor and have little freedom. Heritage says that “persistent institutional weaknesses impede creation of a more vibrant private sector” and “the rule of law is weak.” This sounds suspiciously as if government is too small to do its job properly. But I’m sure that the citizens of Equatorial Guinea don’t mind having a dysfunctional government; after all, they’re lucky duckies.

Perhaps the most interesting part of this short piece – one of the clearest, quickest arguments for the idea that working markets requires a strong, effective government – is that it comes from Bruce Bartlett, a former policy advisor to Reagan, Bush Sr., and Ron Paul. It demonstrates that even someone who has worked with a headstrong libertarian type sees the need for effective government presence in any good society.

The conclusion of his article demonstrates another point however. Bartlett believes that high taxes and low regulation (like Denmark) are preferable to lower taxes and less ‘business freedom.’ So it’s worth keeping mind that, even convincing people that government is important and necessary to a functioning economy doesn’t mean they’ll be convinced that it should be on the side of a functioning society. Still, if you can lead a duck to water…