Earlier this year, a couple of high-level staff at the IMF’s research department and a colleague at the IBRD published a paper on the determinants of long-term growth – that is, of growth spells that continue over time rather than sinking countries into depression and stagnation. Among the determinants they found were: “the degree of equality of the income distribution; democratic institutions; export orientation…; and macroeconomic stability.”

Earlier this year, a couple of high-level staff at the IMF’s research department and a colleague at the IBRD published a paper on the determinants of long-term growth – that is, of growth spells that continue over time rather than sinking countries into depression and stagnation. Among the determinants they found were: “the degree of equality of the income distribution; democratic institutions; export orientation…; and macroeconomic stability.”

That is, the more equal the income structure of the country, the longer the country would be able to sustain growth. The fact that the IMF is now publishing research making this link clear may be surprising, but the result itself is not. After all, Nancy Birdsall has done work for years showing the link between income equality and economic development – she’s even developed a course on the subject! She’s hardly alone. A group of Action Canada fellows (which included Sauvé Scholar alum Sadia Rafiquddin) wrote a well-received report last year pulling much of the literature together, and trying to explore the implications of these insights for Canada. There are lots of good reasons why this might be the case. Even The Economist is getting in on the game!

On the other hand, there is a problem with this entire kind of analysis. Sure, there is the usual normative broadside of “why do we care about growth!?” but I also have a methodological concern I’ve alluded to elsewhere. As two of the authors, Berg and Ostry, make clear in a summary of the equality dimensions of this research, “[t]he immediate role for policy, however, is less clear. More inequality may shorten the duration of growth, but poorly designed efforts to reduce inequality could be counterproductive.”

Such ambiguity fits perfectly with their actual data (so often a repository of key information missed by linear regression): high-inequality countries may not be able to sustain growth, but having relatively low inequality only makes sustained growth possible, not assured.

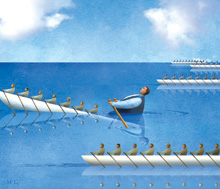

What should be obvious is that the ability of more or less income equality to translate into growth has to do not only with national trade law, or the frequency of elections, or the independence of the central bank. It also has to do with institutions. Strictly speaking, Berg and Ostry’s study, like much of the related literature from recent years, do not ignore institutions, or not exactly.

Somewhere in the background, Berg and Ostry know that institutional structures are at play. Their discussion of “distorted incentives” in Chinese farming policy makes this clear. they totally ignore the qualitative structure of institutions. But by referencing the “quality of economic and political institutions” , they seem to suggest that the role of institutions can be reduced to a single, numerical dimension. Good institutions give people incentives to work (or to save, or to “create jobs”, or to invest in human capital, or in new technology); bad incentives keep people lazy and greedy. Anyone who has had to wrestle with actual on-the-ground policy-making, though, knows that those incentives don’t always line up, and understanding institutions is at the very least about trying to see how people’s incentives coordinate in economic activities, not only whether individuals are inspired to serve the ends of growth.