On Friday night I published a deep dive into Dalhousie University’s finances. While it was a long post, it was limited to trying to explain the university’s financial situation in light of a clear explanation of how the budget works. It left open a few questions about the university’s budgeting policy and budgeting decisions. Here’s the most important one.

In my calculations of how the university paid for its consolidated surpluses over the last ten years, one aspect of my calculations has continued to bother me. Some of the increase came from operational surpluses and carryforwards, but the big part came from capital investment. I needed to explain not only the $349 million increase in the capital fund, but also how the university defrayed $446 million in capital depreciation. I concluded that these funds came primarily from four sources: $331 million from operational spending for campus renewal, $167 million from gifts and grants, $131 million out of capital contributions from ancillary services including rent from student housing, and $77 million from income within the capital fund itself.

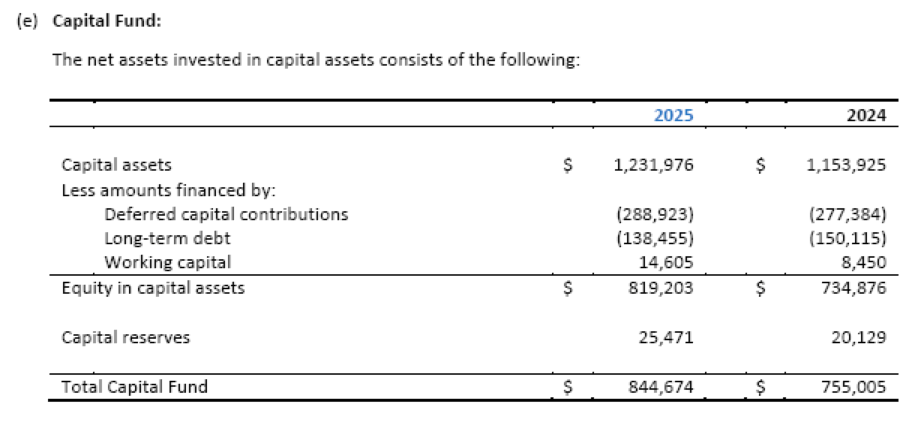

It’s that $77 million I’ve been worrying over. The capital fund is not supposed to generate revenue. As a collection of assets, the fund accounts for the value of physical assets, net of debt and deferred capital contributions. In terms of revenue and expenses, it’s a cost centre. It accounts for interest paid on capital projects and the deprecation of capital goods. Those costs are paid for by donations and transfers from other funds. It is not supposed to have any meaningful revenue of its own. Recall the snapshot of the fund from last year.

Now, there is one way that the capital fund could be said to earn money. Recall that the capital fund contains a small capital reserve, described in financial statements as “funds set aside by the University for the costs of large-scale capital upgrades or replacements planned for the future.” Capital reserves have increased from about $11 million in March 2015 to $25 million in March 2025.

Insofar as these are assets designated as belonging to the capital fund, it is reasonable that the university would also attribute some proportion of its overall investment income to the capital fund. If invested assets earn 5-7% per year, the university might reasonably count 5-7% of the capital reserves as investment income within the capital fund.

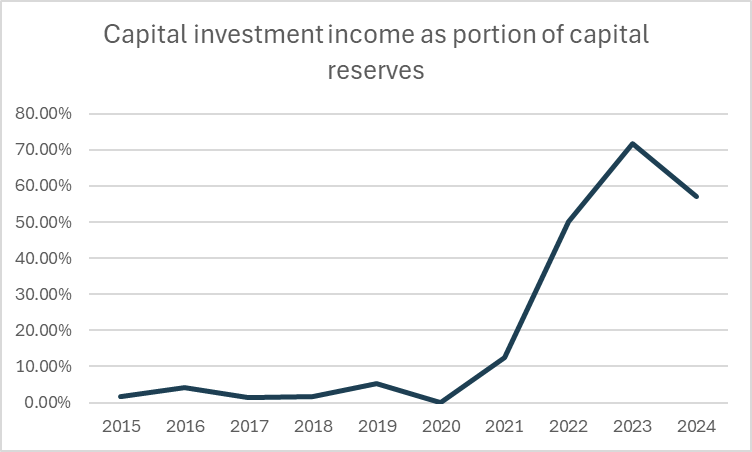

The problem is that the investment income “earned” in the capital fund or, more precisely, the investment income that the (unaudited) schedules to the financial statements designate as revenue earned in the capital fund, bears no consistent relationship to capital reserves over the last ten years. As shown below, designated “capital investment income” was 70% of capital reserves in 2023-24.

Why does this matter? In my break down last week, I essentially argued there are two links between the university’s operating budget and its capital budget, which was key in turn to articulating how the university can have a consolidated surplus, even when the operational budget is in deficit. First, at least once in the last ten years, the board allocated $300 000 from the operating budget to “capital investment” on new infrastructure. (Apparently, they also spent part of an operating surplus on new infrastructure in 2022, including on the new arena). The other link I pointed to are the funds allocated in the operational budget every year for “campus renewal.”

After reading my post, Dan Cohen, who has been active working on faculty budget activism at Queens, pointed out a third possible link between the operational budget and capital spending. Namely, a university might (and apparently Queens did) reallocate investment income to the capital fund rather than to operating fund. The result would be less investment income to spend on operations, lower operational surpluses (or worse deficits), and a corresponding increase in the consolidated surplus, in line with the additional resources allocated to the capital fund.

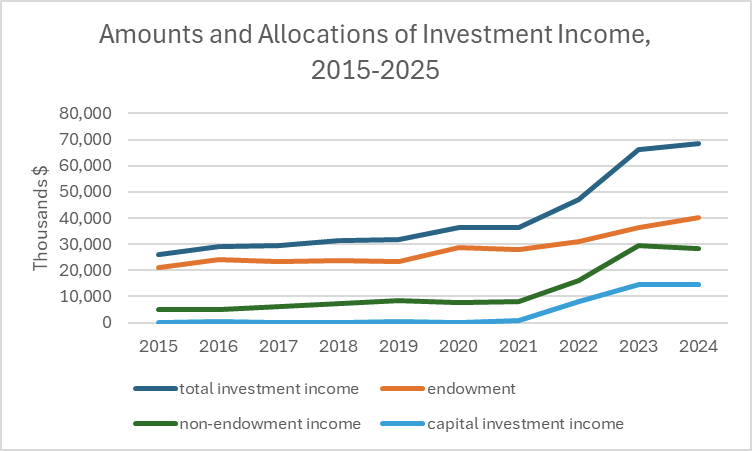

Is this something that has been happening at Dalhousie? Based on the data that I have, it certainly appears to be. Here are the basic facts. As shown in the graph below, total investment income grew gradually between 2015 and 2021, and then jumped radically over the last four years. Recent annual financial reports attribute this jump to a rise interest rates that has allowed the university to earn more from GICs and similar instruments. Between the 2015 and 2024 fiscal years, total investment income increased from $26 million to about $69 million. Much of that income is earned within the endowment, but as total investment income has grown, so has the proportion earned outside the endowment. The university earned only $5 million in non-endowment investment income in 2015-16; that amount was $28 million in 2024-25. How is that income allocated within the university?

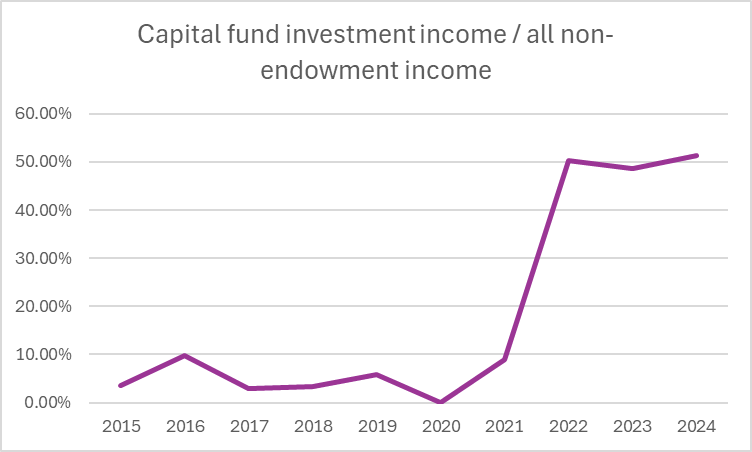

This is the third important change to investment income over the last ten years–really only during the last three years. There has been a massive jump in the portion of investment income designated as having been earned within, and allocated to, the capital fund. That trend is visible in the graph above. I’ve also put it in percentage terms below. The upshot is that an average of about 2% of non-endowment investment income was allocated to the capital fund between 2015 and 2020, while in the last three years, about 50% has been allocated to the capital fund. A cumulative $37 million in investment income was allocated to the capital fund over the last three years. $8 million in 2022-23, $14.5 million in 2023-24 and another $14.5 million in 2024-25.

There may be some perfectly reasonable explanation for this shift. I had considered for example that the change may have been the result of payments from the interest rate swaps used to hedge increases in payments on borrowing for finance capital projects. But that premise is not compatible with either the massive scale of the increase nor with the lack of corresponding adjustments in other parts of the budget reports. It dwarfs changes to the cost of financing.

If there is some consistent or principled rationale of the allocation of investment income, I have not been able to find it. There is no indication in the annual financial statements of how the allocation is being made. And while there are many university policies concerning the governance of endowment funds, there seem to be none that address how non-endowment investment income is to be allocated.

On the evidence I have, it appears that the allocation of non-investment income between operations and capital is being done arbitrarily or, put differently, in accordance with the board’s assessment of strategies and priorities. It appears the board decided over the last three years to allocate $36 million to capital spending, rather than using (more of) that money to fund operational surpluses, build up carry forwards in academic units, and grow reserves. It appears that it decided in particular to allocate $14.5 million in investment revenues to the capital fund in 2024-25–while imposing a hiring freeze, pulling $3 million out of operational reserves, clawing back carry forwards, and running a $6 million operational deficit.

I’ll finish with three hard questions:

- How does the university decide how to allocate its non-endowment investment income? Is there an accounting rule or other policy dictating how that income is to be allocated?

- If the amount of investment income being allocated to the capital fund is more or less up to the discretion of the board, how much investment income is the university planning to allocate to the capital fund next year? Or over the next three years? Notably, $14.5 million per year looks pretty similar to the annual $17 million hole in revenue that is the starting point for the board’s operational budget plan for the next three years.

- If the board made a strategic decision that it was necessary, rational or otherwise in the best interests of the university to spend half of the $70 million in financial windfalls earned over the last three years on capital improvements, on what basis was it decided that this capital spending would be accounted for as investment income earned and spent within the capital budget, rather than as investment income earned in operations and then transferred to the capital budget? Unless there is a good reason, the only conclusion I can imagine is that the board wanted to hide this income during budget consultations and mislead the university community about the actual amount and allocation of revenues available for operations rather than be open about the need for these investments.